Pride in Our Work

![Pride in Our Work]()

Pride in Our Work

![Pride in Our Work]()

A collection of stories from the NDWA Queer Caucus

NDWA is leading intersectional work in the migrant, labor and women’s movements. In 2014, discussions started among staff about another intersection that was close to home to many of us—the LGBTQ movement and LGBTQ rights. An NDWA Staff Queer Caucus was formed in August 2014.

In 2016, twenty people of the current NDWA staff, identified as LGBTQ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer). Since February 2014 we have held a monthly optional Queer Caucus meeting, which has proven the power and possibility of a caucus. The Queer Caucus has been a think tank space to develop and advance an analysis on NDWA’s work through this particular LGBTQ lens. This collection of stories and related curriculum is one outcome of our discussions. Enjoy and be in touch!

by Jill Shenker, NDWA International Organizing Director

June is a month of celebration and honoring for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) people. NDWA works for the respect, recognition, and inclusion of domestic workers and to build a vibrant movement for global justice rooted in a commitment to worker and human rights. Domestic workers come from all walks of life—respect, recognition, and inclusion are not only about labor conditions but also about fighting racism, homophobia, xenophobia, and sexism.

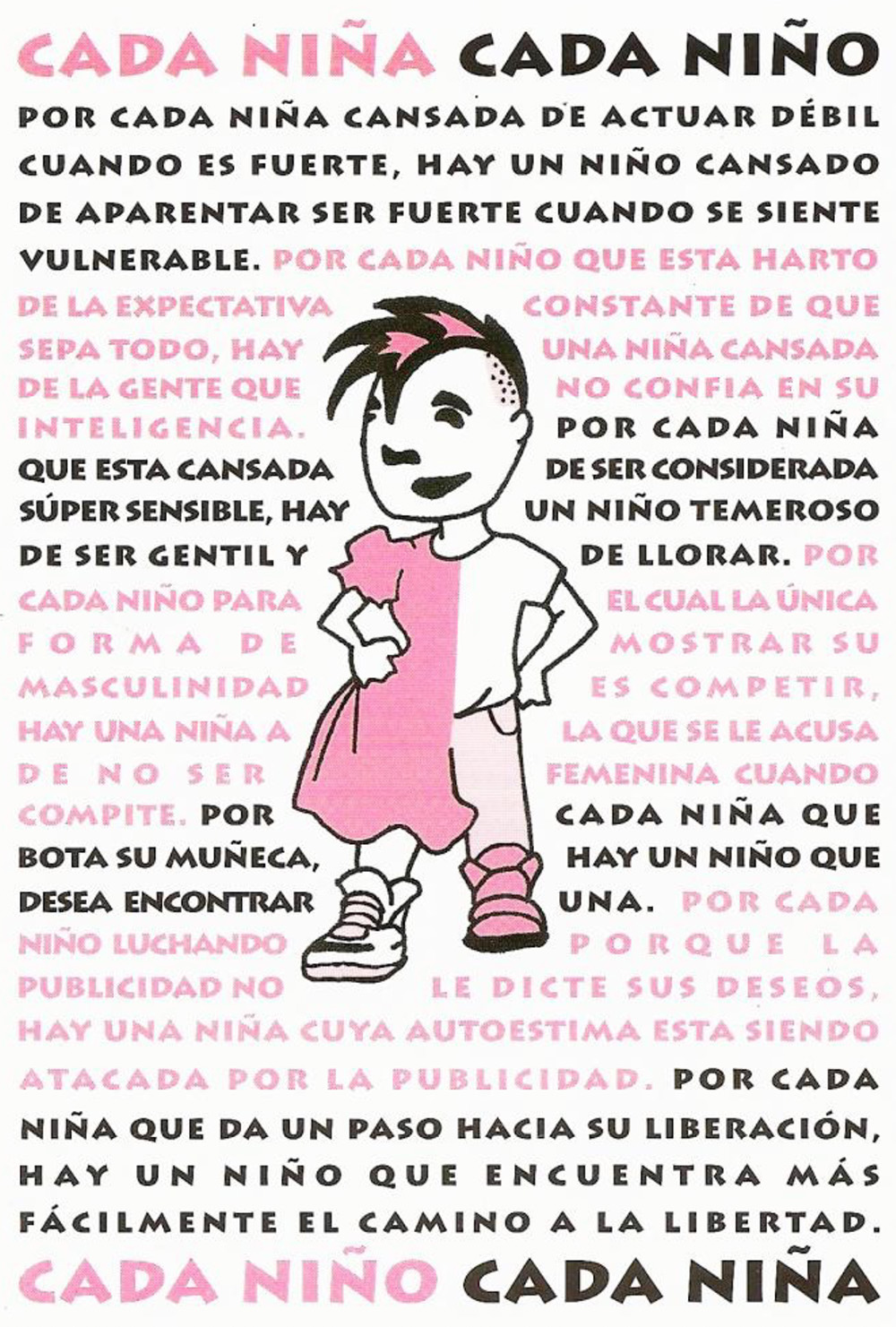

Demeaning and disrespectful notions about women and women’s work shape domestic work and our society as a whole. Patriarchy creates very specific ideas about gender roles—about how girls and boys, men and women are supposed to act, what jobs they should have, their roles in the family, etc. These narrow ideas about gender are connected to an assumption of heterosexuality, marriage, and monogamy, and with it the idea that women take care of the home and can be paid less “because their men are bringing in the real money.” This idea has never been a reality for poor women and women of color and has led to the devaluation of domestic work and the lower pay of women across all jobs. The women’s movement has challenged this assumption through its insistence on women’s right to work outside the home and on equal work for equal pay.

LGBTQ relationships disrupt this norm. When we challenge the assumption of heterosexuality, we also challenge the idea that domestic work, whether paid or unpaid, isn’t “real work,” and the practice of paying women less. Transgender and gender-nonconforming people in this strict two-gender society and economy experience transphobia. People can’t get jobs or can’t get decent jobs, and they are frequently harassed and fired at work.

As we know, women around the world are forced to migrate and work as domestic workers to support their families. For some of these women, migration may mean they are moving to a place where it’s easier to be LGBTQ than it was at home. For example, there is a visible community of LGBTQ migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong and organizations specifically for LGBTQ migrant workers.

Undocumented workers know how challenging it can be to not have legal documentation. If you don’t fit into your legal gender, it is very difficult, if not impossible, and expensive to change your name and gender on legal documents, which affects how you are treated in any situation requiring legal documentation.

Because society degrades domestic work, immigrants, and LGBTQ people, all of these communities face a lot of shame. We all must work to reclaim our dignity and “come out” with pride about who we are. Being visible, lifting up our stories, and making connections is a direct challenge to the system that wishes to keep us small, divided, and ashamed. We will be stronger and more inclusive in our fight for justice, recognizing the connections between domestic workers and LGBTQ people, and respecting and fighting for the rights of LGBTQ domestic workers and organizers.

*Curriculum from SOUL (School of Unity and Liberation) were used as reference for this article.

This is not a complete list of definitions pertaining to this topic.

Sex – The classification of people as male or female. At birth, infants are assigned a sex, usually based on the appearance of their external anatomy.

Gender – A series of social conventions (expectations, conduct, roles) that are usually identified as masculine or feminine. The second feminist movement made the distinction between sex (biological characteristics) and gender (the result of socialization).

Gender Binary System – The idea that there are only two genders – male/female or man/woman and that a person must be strictly gendered as either/or.

Sexual Orientation – Describes an individual’s enduring physical, romantic, and/or emotional attraction to another person. Gender identity and sexual orientation are not the same.

Homosexual – A person who is primarily emotionally, physically, and/or sexually attracted to members of the same sex.

Gay – 1. Term used in some cultural settings to represent males who are attracted to males in a romantic, erotic, and/or emotional sense. 2. Term used to refer to the LGBTQ community as a whole, or as an individual identity label for anyone who does not identify as heterosexual.

Lesbian – Term used to describe female-identified people who are attracted to females in a romantic, erotic, and/or emotional sense.

Bisexual – A person emotionally, physically, and/or sexually attracted to males/men and females/women. This attraction does not have to be equally split between genders, and there may be a preference for one gender over others.

Queer – “Queer” is a reclaimed word that was formerly used solely as a slur but has been taken up by members of the maligned group who use it as a term of defiant pride. For decades, ‘queer’ was used solely as a derogatory adjective for gays and lesbians, but in the 1980s, the term began to be used by gay and lesbian activists as a term of self-identification. Eventually, it came to be used as an umbrella term that included gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, and transgender people. Nevertheless, a sizable percentage of people to whom this term might apply still hold ‘queer’ to be a hateful insult, and its use by heterosexuals is often considered offensive.

Homophobia – Derived from the Greek for “same” and “fear.” It refers to the fear/hatred toward lesbians, gay men, and bisexual people.

Heterosexism – The system that normalizes and maintains heterosexual conduct and heterosexual relationships to the detriment of human conduct and relationships of a sexual orientation different from the heterosexual (for example, state benefits for heterosexual married couples).

Gender Identity – One’s internal, deeply held sense of one’s gender. For transgender people, their own internal gender identity does not match the sex they were assigned at birth. Most people have a gender identity of a man or a woman (or a boy or a girl). For some people, their gender identity does not fit neatly into one of those two choices.

Transgender – Derived from the Latin word for “crossing.” An umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from what is typically associated with the sex they were assigned at birth. People under the transgender umbrella may describe themselves using one or more of a wide variety of terms, including transgender. It is regularly abbreviated as “trans.” Use the descriptive term preferred by the individual. Many transgender people are prescribed hormones by their doctors to change their bodies. Some undergo surgery as well. However, not all transgender people can or will take those steps, and a transgender identity is not dependent upon medical procedures.

Transsexual – An older term that originated in the medical and psychological communities. Still preferred by some people who have permanently changed or seek to change their bodies through medical interventions (including but not limited to hormones and/or surgeries). Unlike transgender, transsexual is not an umbrella term. Many transgender people do not identify as transsexual and prefer the word transgender. It is best to ask which term an individual prefers. If an individual prefers the use of this term, it should be used as an adjective: transsexual woman or transsexual man.

Transphobia – Fear of or hate toward people who do not meet gender conventions.

Coming Out – May refer to the process by which one accepts one’s own sexuality or gender identity (to “come out” to oneself). It may also refer to the process by which one shares one’s sexuality or gender identity with others (to “come out” to friends, etc.). In recent years, undocumented immigrants have adopted the term when referring to a public sharing of their immigration status.

Discrimination – Prejudice + power. It occurs when members of a more powerful social group behave unjustly or cruelly toward members of a less powerful social group. Discrimination can take many forms, including both individual acts of hatred or injustice and institutional denials of privileges accorded to other groups. Ongoing discrimination creates a climate of oppression for the affected group.

LGBTQ Ally – Someone who confronts heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, heterosexual and gender privilege in themselves and others; someone who has a concern for the well-being of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people; and someone who believes that heterosexism, homophobia, biphobia, and transphobia are social justice issues.

* We used various resource to write these definitions, including curriculum from the School of Unity and Liberation (SOUL), and http://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender

Member of Fe y Justicia Worker Center

My name is Lisandra Hernández. I was born in the state of Veracruz in México. I came to the United States seven years ago.

My name is Lisandra Hernández. I was born in the state of Veracruz in México. I came to the United States seven years ago.

When I turned 23, I decided to stop hiding my sexual orientation, and I decided to share this decision with my family and friends. I thought the US would be a place where I could live freely with my sexual orientation, and I thought that in coming to this country, I would leave behind the prejudices I had to deal with in my own country.

However, when I decided to immigrate, I never imagined that my sexual orientation would also lead to barriers finding and keeping a job in this country.

At each job interview, I got more and more stressed out. I was always afraid that I would be judged for my sexual orientation, and my skills and abilities would be overlooked. I applied for work at a car wash, and there I was a victim of sexual harassment by my supervisor. During the interview, everything was great; the supervisors were really happy to have me as part of the team because I had seven years of relevant experience and I was a really dedicated employee.

But my success didn’t last very long. The first week, my supervisor tried to approach me in a way that was different from how he approached the other workers, with exaggerated smiles, looking for moments to be alone with me to flirt and invite me to have alcoholic drinks with him after office hours.

I felt very perturbed by his attitude and decided to tell him about my sexual preference and ask him to stop the insinuations towards me, which made me uncomfortable. The supervisor retaliated against me for being a lesbian. First, he told me that I was wrong about my sexuality, and that he was going to show me that I really liked men.

I told him that I was not interested, and seeing that he did not get what he wanted, he began to make fun of me with his coworkers about my sexuality and to give me heavier work, work that was normally performed by men. In order to preserve my job, I did all the work I was assigned, knowing that an excessive workload was a consequence of having told him about my sexual preference and having rejected my supervisor’s propositions.

Fed up with so much stress and pressure at work because of my supervisor’s harassment, I decided to report it to his superiors, but I never got any response from them. After that, my supervisor didn’t want to pay me for two weeks of work that I was owed, and when I demanded my check, he told me that since I was undocumented, he was going to keep my check. He already owed me $700, but what he really wanted was for me to give in to him.

That’s when I decided to find help to get the wages I was owed. I ended up at the Fe y Justicia Worker Center a year ago, and they showed me how to file a wage theft complaint, an OSHA complaint for the chemicals we were using, and a discrimination complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). I felt safer and more confident after that, and I realized that I didn’t have any reason to feel ashamed of my sexual orientation. I learned that I have rights, and I exercised them by filing all those complaints.

After that, I got a job cleaning apartments, and I got more involved in the worker center and the Colmena domestic workers project. I’ve participated in workshops, protests for the Fight for 15. I was able to go to New Orleans to defend DACA/DAPA because in this country, I didn’t just find the same prejudices and harassment because of my sexual orientation that I had faced in my own country. Here, I am also seen as a criminal because I don’t have papers.

As I’ve gotten more involved with Fe y Justicia and with the other domestic workers in La Colmena, I’ve gained the strength to tackle all of the injustices, barriers, and discrimination that I face as a woman, a Mexican, an immigrant, a low-wage worker, and because of my sexual orientation. I’ve also faced disrespect because I’m in a same-gender relationship, and now, with all the uncertainty around DACA/DAPA, I’m suffering from the same lack of rights that all other immigrants experience.

I’ve learned that my sexual orientation and undocumented status are not offenses or crimes; they are differences that the system uses to oppress us. That’s why I stay active and committed to the movement because I’ve learned that only through struggle will I be able to thrive as a woman, lesbian, and immigrant. Struggling together with others, we’ll be able to change things and guarantee the rights and equality that we deserve.

Member of Casa Latina – Seattle, WA

“I always knew I liked boys and that I liked to dress up.”

Unfortunately, for me in my childhood, I was physically, verbally, and mentally abused. My mom never supported who I was – she always knew that I was going to be gay. And I always knew I liked boys and that I liked to dress up. I don’t know if I was especially abused because I was her only kid from her first marriage or because of my sexual and gender identity, but I was treated worse. I knew who I was and what I wanted, but I wasn’t understood. When Three Kings Day arrived, I wanted dolls. I used to trade my sisters for their dolls and tea sets.

I came to the US in 1987. I was already married – things didn’t work out for obvious reasons. My cousin told me he got a ticket for me, so it wasn’t really a decision, but I guess it was kind of to escape my marriage. I went to Fresno, CA. I was 17, and I worked in the fields until I was 21. I was in the closet, pretending to be a straight guy. I didn’t start coming out until I moved to Seattle where I didn’t know anybody. It was easier for me to be somewhere where no one knew me. I could do whatever I wanted and nobody would notice. So, I came out, and I started living my gay life. I can remember exactly the day I decided I wanted to be a transsexual. I connected with this organization called Entre Hermanos Latinos. We marched for gay pride, and I was dressed up. We were with another friend, dancing with 6-inch high heels on. Everybody cheered. It felt so great! This is me! That’s who I am. I’m not gonna hide anymore. I just want to do what my heart tells me to do. That’s when I decided to become a transsexual. I didn’t transition until I was almost 30 years old. It’s been ups and downs since I made that decision. It turned my life around completely, changed everything. It’s not easy, but I don’t regret it. I think that’s the best decision I’ve made in my life. It hasn’t been easy.

My family has accepted me, but it was hard. When I was a boy, I would hide myself. That’s why I got married, had a lot of girlfriends. When I was telling my brother, he said, “I know.” They always knew. I had spent so much energy pretending, but everybody knew I was gay. I learned about accepting ourselves for who we are. That can be the hardest thing.

I worked as a housekeeper for many years and got connected with Casa Latina. When I came to NDWA events, I would feel nervous, wondering how people are going to see me, treat me, react. It was a very good experience for me. Everybody respected me, treated me right, and I got to meet a lot of great people.

I haven’t been participating in Casa Latina for a while. A couple of years ago, there was this guy who was just homophobic. He would talk behind my back, which I just had to ignore. One time we got into a confrontation at the weekly membership meeting. He was insulting me in front of everyone, and we got into an argument. I felt really bad. Half of the day laborers were with him, even though he was talking shit. Of course, I reacted – I had to defend myself. I felt really bad because people were supporting his crap, saying I was rude, but didn’t talk about why I reacted. Maybe it wasn’t the best way to react, but I was pushed to it. Casa Latina backed me up 100%, but we both got suspended.* I got really disappointed and stopped being active, even after the suspension ended. I was really upset. That guy never came back either.

Unfortunately, the majority of discrimination I’ve experienced is with my own people, with Latinos. We have to stop discriminating against each other. Sometimes I want to go back and become a member again to help and be part of it.

Since then, I went back to school and got my GED. I want to have a career as an interpreter.

*Note from Casa Latina: Kassandra was sanctioned according to the rules of conduct of the Work Center of CL for one week for a lack of respect. In the meantime, the male worker who provoked and insulted her was suspended for one year and needed to, as a condition to return to the organization, take training about the rights of the LGBTQ community provided by the Office of Civil Rights of the City of Seattle.

Member of Mujeres Unidas y Activas San Francisco, CA

My name is Monica Gonzalez, and I’m a member of Mujeres Unidas y Activas in San Francisco. I want to share a story about the love I have for my son, Roberto, who is twenty years old. Since he was born, we always had a really strong connection. When he was born, we were all so happy. When he was thirteen, I started to suspect that he was different. He liked to play with dolls, and my family would always get mad at him and say, “You’re not a fairy, don’t go playing with dolls.” When he got to elementary school, he would always play with the girls, and when I would ask him about it, he said he didn’t want to play with the boys.

My name is Monica Gonzalez, and I’m a member of Mujeres Unidas y Activas in San Francisco. I want to share a story about the love I have for my son, Roberto, who is twenty years old. Since he was born, we always had a really strong connection. When he was born, we were all so happy. When he was thirteen, I started to suspect that he was different. He liked to play with dolls, and my family would always get mad at him and say, “You’re not a fairy, don’t go playing with dolls.” When he got to elementary school, he would always play with the girls, and when I would ask him about it, he said he didn’t want to play with the boys.

When he got to middle school, the children were always criticizing him. They hit him, and he didn’t defend himself. I went to the school and spoke with a teacher who told me that if my son was gay, he just had to say so, and nobody would bother him. I got very angry because I thought that my son had the right to say so in due time and if he wanted to, because I knew that it was not going to be so easy.

When he got to high school, it was more of the same. He didn’t want to go to the bathroom because the other kids pushed him and hit him. I used to say to him, “Don’t pay attention to them. I will always be with you, no matter who you are.” But even so, he didn’t want to tell me about it. One time, some kids left him messages about how they were going to kill him, that this was his last day. They said, “Go to the Castro; that’s your place.” I only realized this because my daughter listened to his messages and told me. He did not tell me anything about it, but I noticed that he was nervous. I went to the school to speak with the director, and when my son saw me, he told me that nothing was wrong and that it was a joke. But I knew that was not true.

When he graduated from high school and started college, he finally started to seem a little more at ease. Two years ago, he told me that he wanted to talk to me. He said, “Whatever happens, I love you, and I respect your opinion, but I have something I need to tell you.” At first, he told me that he liked both women and men, that he was bisexual. I told him, “Congratulations, son. I support you. I’m your mother, and I will never reject you.” Then later, he once again told me that he wanted to tell me the truth, and this time he told me he was gay. My answer was the same, that I would love him through thick and thin. He said, “Thank you for understanding me and believing in me. I thought you would reject me and throw me out of the house.” I told him, “I love you,” and I hugged him.

Later, he told me that his work was going to be different. He’s 21 now, and he wants to work as a drag queen. He told me, “I’m gay, but I like drag shows. That’s what I’m going to do for work. I’ll be dressing as a woman. It’s a job. But I’m gay because I like men. I’m not transgender. This is a job that I’m going to do to get ahead.” He showed me photos of a young woman, and I asked him, “Who’s that young woman?” He laughed and told me it was him! Now he tells me that he wants me to come along when he goes to work. I think he wants me to carry his costumes and wigs!

My fear is that someone could do something bad to him. I know that there are some people who hate gay people, and that worries me a lot. I’ve learned so much from him about how to treat lovingly gay and lesbian people, especially young people. I know I shouldn’t criticize them; I must treat them just like any other human being. The only advice I can offer other mothers is to listen to your children, accept them as they are, and love them.

Organizer with Damayan New York, NY

I am in Washington, DC for a retreat for the Beyond Survival Campaign, along with four trafficking survivors, leaders of Damayan, and we are about to leave the rental house. We are going to the campaign report launch, and as such, we are appropriately dressed. I’m in a suit jacket, tie, and pants. Before leaving the house, one of the workers, Judith, stops me at the door to adjust the fold at my pants. “Sandali – ayusinkomunaangbinata (wait – let me fix our young man).” We all laugh heartily.

I am in Washington, DC for a retreat for the Beyond Survival Campaign, along with four trafficking survivors, leaders of Damayan, and we are about to leave the rental house. We are going to the campaign report launch, and as such, we are appropriately dressed. I’m in a suit jacket, tie, and pants. Before leaving the house, one of the workers, Judith, stops me at the door to adjust the fold at my pants. “Sandali – ayusinkomunaangbinata (wait – let me fix our young man).” We all laugh heartily.

As a masculine-of-center, queer woman, I am often mistaken for a man. We call this misgendering – referring to someone by a gender to which they do not identify. It’s most often unwelcome. But the type of joking that happens in Damayan, when spoken with affection by workers who know me well, signals a kind of acceptance and openness. Workers like to show me pictures of their daughters who are “like me”. I sense a pride that I hope their daughters know their mothers have. One of our leaders has a daughter who is a “tomboy” (in the Philippines, “tomboy” means lesbian), and she calls me her daughter because she says we look similar. She talks to me – sometimes through tears, sometimes with laughter – about what her daughter is like, how she misses her daughter and her grandchildren (this daughter has two children with another woman). She hasn’t seen them in three years; she hasn’t met one grandchild yet. As a trafficked worker, she will soon receive her T visa, but her daughters are over-age for the T visa derivative, and she will have to wait another three years for her green card in order to go home to the Philippines and see her family.

Personal connections mean a lot to me as an organizer. I come to this work as my complete self. Workers, who open up their deepest traumas to the organization and trust in the organization completely, know my story as well as I know theirs. I believe that in order to be lasting and strong, we have to build our movement on authentic connection. But let’s get at the systemic issues. At a recent leadership retreat, Damayan held a workshop on anti-LGBT violence, where workers recognized commonalities between the violence experienced by LGBT folks, by women, and by workers on their jobs. We showed a video showing photos of trans people whose lives were lost in anti-transgender violence, so many of them youth and children. Several of the workers were brought to tears; most were not aware of how much violence trans people face. Queer folks appear in popular Filipino culture mostly as entertainment and for comedic effect. But what about queer and trans domestic workers? What about the particular violence and discrimination they face as they cope with multiple oppressions? These are the types of questions we ask in Damayan and discuss with our members.

I recently asked Judith to join Trans Day of Action here in New York, taking place in two weeks. Without hesitation, she responded, “Oonaman! (Of course!)” Here’s to a joyful and just Pride Month.

La Colectiva de Mujeres, San Francisco, CA

Guillermina Castellanos, Organizer with La Colectiva de Mujeres, shares how they’ve been able to create an environment that is respectful and welcoming for all.

La Colectiva de Mujeres is an organization made up of domestic workers, mostly Latinas, in San Francisco, which is connected to the Day Laborer Program. At every meeting, we repeat our mission and vision, which is closely related to the organization’s founding principles. We say that everyone is welcome and respected, regardless of race, religion, nationality, sexual orientation, gender, etc. When we do introductions, every woman says the mission in her own words and welcomes new participants. It’s a culture that we’re creating – it’s like reviewing a family’s values.

The value that La Colectiva provides is the value that every human being needs – dignity and respect. And we share everything from food, beliefs, culture, emotions, and traumas. We come to an understanding that taboos aren’t helpful in the creation of a better world. That helps us reflect on the fact that we are all equal because we are all human beings. And so we establish the fact that all human beings have the right to be just as they wish to be.

Member of La Colectiva de Mujeres

My name is Andrea Manzo, and I live in San Francisco, CA. As a result of a really difficult situation I was facing, I was referred by another agency to La Colectiva de Mujeres. I’ve been a member of La Colectiva since 2013. I came to the group with low self-esteem and fear because of the abuse and attacks that members of the transgender community are subjected to.

The thing I like the most about La Colectiva is their mission and vision. La Colectiva supports all members, regardless of gender, race, religion, or legal status, and it teaches us to be independent and fight for domestic workers’ rights, social justice, and human rights.

Also, through their hiring hall, we can provide for ourselves, meet our basic needs, and support our families back home. We also have a “Soul Group” that covers issues related to self-esteem. There we can all share our problems and traumas that affect our daily lives – related to work, family, partners, domestic violence, legal issues, or any other type of problems that we may be dealing with. In general, I really like the “Soul Group.” Talking through my problems helped lift my self-esteem. It’s a confidential group, and my sisters there understand me and don’t judge. I’m really proud and grateful to be a member of La Colectiva de Mujeres. Thank you to La Colectiva for existing and for changing my life.

Member of La Colectiva de Mujeres

My name is Flavia Sánchez. I’m a transgender woman who came to La Colectiva in March 2014, during a really difficult time when a romantic relationship I was in was ending, and the company where I had worked for almost four years was having a downturn, resulting in me losing my job. This whole situation left me with deep depression, to the point that I could hardly get out of bed to take care of basic activities.

My name is Flavia Sánchez. I’m a transgender woman who came to La Colectiva in March 2014, during a really difficult time when a romantic relationship I was in was ending, and the company where I had worked for almost four years was having a downturn, resulting in me losing my job. This whole situation left me with deep depression, to the point that I could hardly get out of bed to take care of basic activities.

Through one of life’s coincidences, I got in touch with somebody who invited me to one of La Colectiva’s weekly Wednesday meetings so that I could get to know new people and maybe find a job. I had no idea how the organization functioned.

The day of the meeting arrived, and I started to feel a little uncomfortable because most of the women there come from a culture and a country that’s very different from my own. I’m Cuban, and my customs and culture are really different. I kept my distance for the first couple of weeks, mostly reserved and pensive. I said to myself, “What am I doing here? I’ve never worked in house cleaning. I don’t think I belong here.” Thank God I learned at home how to cook, clean, and keep my home in order. I thought maybe that would help me through this new phase of my life. I was thinking about not working anymore and filing for disability. I really didn’t know what the future would bring.

Things started happening little by little without me realizing. I started to feel better and get more involved in the organization. I was invited to join a committee and take on more decision-making in La Colectiva’s projects. I was given the opportunity to travel to Los Angeles to represent La Colectiva in a big event with organizations from all over the US. It was an experience that I’ll never forget, where I received a lot of training and learned a lot about other organizations. When I returned, I had a lot of work waiting for me since, thankfully, a lot of the houses I had cleaned for the first time wanted me to come back.

In terms of integrating myself as a trans woman, I think I was very well received. I like to think of myself as someone who is respectable, and therefore, I gain most people’s respect and affection. Obviously, like in any place, there were some rough spots. You can’t always be liked by everyone.

I’ve also been very lucky to be well received in the homes where I am currently working, without any problems. I believe that also because of my totally natural behavior from the start, many of them did not even notice it – many of them becoming surprised when they found out. Obviously, this gave me great satisfaction because my projection was the right one, and I was not seen as the negative stereotypes of trans women who are seen as transvestites or vulgar people.

La Colectiva took me under her wing, gave me valor and strength to keep fighting against adversity. Thankfully, I’ve also been able to get a lot of work. I think it’s important to remember what working can give you. I think when you’re feeling strong and in a good and stable place emotionally, you can get past any obstacles that life puts in your way.

Allison Julien, Organizer with We Dream in Black, NY

As someone who works and lives in a world with all “different” kinds of people, it came as no surprise to me to learn of nieces, nephews, relatives, and friends who identify as LGBTQ. I have been able to see firsthand how “coming out” has been mostly perceived in a negative way by family members and the community. As people, when others are seen as “different,” they are often ostracized with little thought to the emotional trauma inflicted. The effects of unkind words, actions, and pain caused because of a lack of knowledge, religious beliefs, or malicious intent inspire me to be a strong voice and a consistent listening ear in support of their journey. Pain is real, and love is real. We have to remember we are all human beings first, and all the additional components are the “sprinkles” on top.

An Interview with LETICIA ÁLVAREZ Organizing Director

The Tennessee Immigrant and Refugee Rights Coalition (TIRRC) is a statewide, immigrant and refugee-led coalition that has empowered individual and organizational members to develop a unified voice, defend their rights, and create an atmosphere in which they are recognized as positive contributors to the state. Over the past several years, TIRRC’s organizing team has developed local organizing committees in cities across the state. Currently, TIRRC’s Organizing Director, Leticia Alvarez, is working with thirteen Latino organizing committees in Tennessee. While historically these committees had been defined by city, three years ago Leticia founded the Committee of Immigrant Women of Nashville, a group of Latinas who organize for social justice from their unique experiences as immigrant women. Two months ago, Leticia worked with local community leaders to found a local organizing committee specifically for LGBTQ immigrants. Leticia talked with us about how this program came into being and her hopes for where it will go.

For years, LGBTQ immigrants have been involved as leaders in our work and in our local organizing communities. But while many LGBTQ members have been on the front lines of our campaigns for immigration reform and immigrant rights, we never engaged in intentional work or specific campaigns around the unique experiences of LGBTQ immigrants. I was approached recently by a man who was a former member of a youth group I coordinated years ago. He’s in his 30s now, has come out of the closet, and wanted my support in creating a film about homophobia. Through those conversations, he suggested that we start a group. Over the years, other members have talked about the need for this kind of space, too. And while I saw the need for this kind of program, I didn’t feel like I was equipped to create it myself because I didn’t have any resources or materials to work with, and I myself don’t identify as LGBTQ. But after a few conversations, we decided to go for it and launched the group in Nashville about two months ago.

Over the past two months, the group has met every Monday for two hours. We decided that it could be really informal, and that we would just provide this space for immigrants who identify as LGBTQ to come together. We wanted it to be participant-led, but upon the members’ request, we have partnered with a local mental health organization that has provided some counseling and support to the group. The group is still forming and setting a vision for their work together and in the broader coalition of TIRRC. After two months, we have about 8-12 members who meet each week. They’re a diverse group in terms of age, immigration status, and country of origin.

It’s a space for them to talk about the discrimination they face as LGBTQ people who are also immigrants. People are able to share their experiences about being discriminated against in their workplaces because of their orientation. I also want to help the group develop their message and materials so that they can represent themselves and their group publicly. The members of the group—especially the youth—want some materials that can help them to educate their own family members. I’ve heard from some of the participants that they had tried to access other LGBTQ organizations, but that they felt like those spaces weren’t for them because the people in those other groups didn’t understand what it is to be an immigrant and also be LGBTQ. This group is really different because everyone understands that particular combination of identities.

It’s hard because we really don’t yet have the right materials for this group. In our broader organizing work, we do a lot of political education and have developed curriculum over the years. But right now, we are still looking for popular education tools for the group to use in developing their own vision and analysis together, and also political education materials for our other organizing committees and member organizations to learn and be in solidarity with this new group. We have a very diverse coalition that includes immigrants and refugees of many different faiths, cultures, and countries of origin who may not immediately understand or support why we would organize an LGBTQ committee. These are hard but critical conversations for our coalition to have.

In addition to needing these particular resources, it would be helpful for us to hear the experiences of other immigrant rights and workers’ rights organizations that have started LGBTQ organizing programs. We’re really just learning as we go along and can learn from other groups.

It’s really easy to feel like you can’t start a program like this because you don’t have special funding for it, or you don’t have all the materials or experience you need. My advice is to not think about those barriers! Think instead about what you can learn along the way. Once you open the space for this community to come together, so much creativity and so many ideas come from the participants themselves. We are very excited about deepening and broadening this work and look forward to connecting with other groups who are working for immigrant and LGBTQ rights.

Isa Noyola

In May 2015, five LGBTQ immigrant rights leaders conducted a civil disobedience in front of an immigrant detention center in Santa Ana, California, that detains LGBTQ immigrants. They took action and got arrested in order to demand an end to unjust detentions and deportations, particularly of undocumented LGBTQ immigrants, and the release of all transgender women in detention.

Across the country, there are over 904,000 adult LGBTQ immigrants, and more than 267,000 are undocumented. On any given night, around 75 transgender immigrants are detained by ICE in immigrant detention centers. Many of them are transgender women seeking asylum and fleeing violence and abuse in their home countries. Transgender women only represent 1 out of 500 immigrants in detention, but they represent 1 out of every 5 confirmed sexual assaults reported inside the detention facilities.

Below, Isa Noyola, one of the leaders who participated in the civil disobedience protest in Santa Ana, talks about the action and why we need undocuqueer and transgender people leading the migrant rights movement and the struggle for dignity and liberation for all communities.

Isa Noyola is Program Manager at Transgender Law Center, where she works extensively for the release of transgender women from ICE detention and an end to deportation. Isa identifies as a translatina, activist, two-spirit, queer, jota, pastor’s kid, muxerista, and cultural organizer. Isa is passionate about abolishing oppressive systems that criminalize trans and queer immigrant communities of color.

“On May 28th, I risked arrest as part of the #Not1More LGBTQ Deportation Rally, blocking the road in front of the Santa Ana transgender detention pod, to demand that Immigration and Customs Enforcement end the torture and rape of trans immigrants who are inside ICE detention centers. The story of many transgender communities is one of immigration and of suffering mental, physical, and sexual violence while housed inside ICE detention centers. Transgender women must be on the frontlines of this fight for #Not1More deportation and for the collective liberation of our communities. And our voices must be heard, no matter what, even if it means putting myself at risk of arrest.

Last year, when I attended a major national immigrant rights conference, I found myself in many workshops and plenaries being the sole voice advocating and raising the issues of immigrant trans women of color in detention. There were no trans immigrants leading workshops or any immigrant trans women of color on plenaries or giving speeches. This has been my experience in this last year – I am one of the few voices nationally bringing attention to the issues immigrant trans communities face, demanding justice, and calling for intentional allyship.

Changing this reality and highlighting the resiliency of powerful trans immigrant women has been a key focus of my work. Adding a trans woman of color lens and deeper understanding of gender strengthens our advocacy. The transgender community has a rich herstory of resistance and existence in the organizing world, and it is time to reclaim that herstory and space.

Today I am proud to put my own liberty on the line to advance liberation for all trans immigrants. That doesn’t just mean ending the horrifying abuses transgender women face in immigration detention, although that is a huge part of it. It also means ensuring trans immigrant women are able to live and thrive in this country after they are released from detention. Recently, for example, advocates secured the release of Nicoll Hernandez-Polanco, a young Guatemalan trans woman who had been placed in a detention center with men. Nicoll is now free from the abuse she suffered there but has no housing and is staying with one of the activists who organized for her release. That is not a comprehensive plan for liberation for our community. We cannot just shout #FreeNicoll – we must also work towards creating a system to support her and other trans women as they navigate life post-detention.

Racial, environmental, economic, and immigrant justice work is transgender justice work. I believe now more than ever, as I rally here in Santa Ana, that our voices and leadership are needed to strengthen the work so that we may deepen the analysis of oppression that is violently attacking us at every turn.”

Tell us your story about how domestic work and LGBTQ lives are connected for you! For example, share your experience working for an LGBTQ family, being a domestic worker who is LGBTQ, or being a family member of an LGBTQ person.